|

“I’m good in practice but I can’t seem to get the results in games.”

“Our team seems to be improving but it’s not really showing in games.” These are common statements made by players, coaches and parents alike. So what’s going on here? Why does this seem to be a growing problem? The issue stems from these reasons: 1. Growing popularity of “trainer culture”; more players now work with a private (1on1) skills trainer who helps them develop skills in a controlled and predictable environment (generally no defense). 2. Coaches who want things to look neat and tidy at practice. This usually results in lots of unrelated drills where players are performing predetermined skills (often in ways that don’t resemble the game at all). The problem is games are messy. 3. We focus on the wrong things. The goal of any player should be to get better at things that happen the most in the game. I think we (adults in the basketball community) have steered players astray on this one. Extensive dribble combo moves, high degree of difficulty shots etc. are generally a waste of time for 95% of players. This does not even account for the time that gets wasted at practice when coaches spend too much time working on set “plays” rather than developing skills (which includes decision-making). Having a playbook of “plays” that players cannot execute because of a skill (decision-making) deficit will not help you improve individually (or as a team). So it’s easy to state what’s not working - let's look at an alternative approach that actually does transfer to the game. First, let’s distinguish between kind and wicked learning environments. Kind environments, as defined by psychologist Robin Hogarth, are “where patterns recur, ideally a situation is constrained – so a chessboard with very rigid rules and a literal board is very constrained – and importantly, every time you do something you get feedback that is totally obvious, all the information is available, the feedback is quick, and it is 100% accurate….And in these kinds of “kind” learning environments, if you’re cognitively engaged you get better just by doing the activity.” Golf or chess would be kind environments. However, wicked environments, which is where basketball would fall, often have information that is hidden. Even when it isn’t, feedback may be delayed, it may be infrequent, it may be nonexistent, or it maybe partly accurate or inaccurate in many of the cases. There are no built-in rules and recurring patterns - it cannot be automated like chess (if A, then B). Basketball is a series of unique and random scenarios that unfold throughout a game. Again, the problem is we are training basketball players as if it’s a “kind environment” when in reality it’s very much a “wicked” one. The antidote to kind learning environments that don't transfer to the game: Constraints-based training. This method of practice uses constraints (individual, environmental and/or task) to maximize learning a given area of the game. An example could be constraining the physical size of the court, limiting the number of dribbles or modifying the rules slightly. Players would still be playing the game amidst these constraints but their focus would be drawn to certain elements of the game in a constrained environment. Contrast this approach with traditional drills that essentially pluck random skills OUT of their game context with the hopes that once you go to apply them in a game context they will show up - unfortunately, the transfer is minimal. They are different tasks. And the biggest reason for the lack of transfer with standard “drills” is the absence of decision-making. You cannot separate the decision from the skill - someone is only a good shooter if they generally know when (and when not) to shoot (and obviously are able to make a respectable % of the shots they do decide to take). Simply having good shooting technique or making shots in a kind environment does not make someone a good shooter. So there it is, play more games to learn how to play the game. Sounds simple doesn’t it?! The art of coaching comes in with what constraints to use and when. All of our group based programming is designed with a constraints-based approach and we’ve seen fantastic results adopting this way of teaching. We would be happy to discuss how you too can begin to adopt this approach to training with your team or club.

0 Comments

“No, I won’t train your child 1 on 1”.

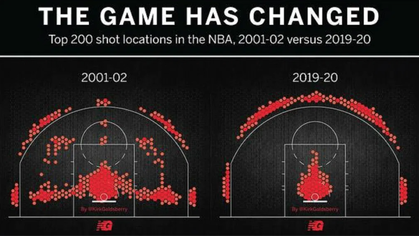

I’ve found myself saying that a lot lately so I wanted to unpack the “why” for families, coaches and players alike. Basketball is not piano. It’s common for parents to enroll their young kids in piano lessons as a way of learning how to play the instrument. The piano teacher gives all of their attention to the child, shows them how to play, they improve and maybe even become lifelong pianists. Money well spent! That line of thinking often gets used when trying to improve at basketball. But it’s wrong. Basketball is a team sport. You aren’t preparing for a 1-person showcase (recital) as a basketball player. The game is dynamic and it is played alongside 4 other teammates (and 5 opponents). For the sake of simplicity I will give 3 main reasons why 1on1 basketball training is at best ineffective and at worst a huge waste of time and money for parents (of young players). These reasons assume that the main goal of 1on1 training is to perform better in games. If the goal is purely social or simply to enjoy the game more then maybe 1on1 training can serve those purposes. 1. Lack of decision-making Basketball, like any team sport, involves hundreds of little decisions throughout the course of a game. When do I make this pass? What kind of pass should I use? Should I shoot, pass or drive? Will I have time to make one more move or do I pick up my dribble now? You can’t simulate those decisions with no live defenders. Not to mention where you dribble the ball, how you position your body, where you scan with your eyes are all based on where your defender is and where the other players are on the court. A bright orange cone provides a very poor replacement for a human in these scenarios. Bones>Cones. Most players (especially younger ones) don’t have the experience and prior context to imagine where defenders would be, when this move would work and how to execute it in real time. Therefore, practicing offensive moves in a 1on0 setting has very limited transfer to the game. Essentially, how something is being practiced is not how it will be executed in a game situation. It begs the question, why practice it in the first place? 2. Skills they won’t be able to use (in games) More often than not a player is being trained by someone other than the coach of their team. And unless this trainer communicates directly with the coach of the player’s team then they may be working on skills and concepts that the player won’t even have the freedom to execute come game time. This one can mostly be mitigated with open communication between the trainer and coach but from my experience these conversations rarely happen which leads to a disconnect between what’s being practiced and what the player is able to perform in a game (based on their role within their team). In addition to the reason above, the skills worked on in a 1 to 1 session are often exclusively on-ball (meaning things that happen when the player has the ball in their hands). But we know that 95%+ of the game happens when you do NOT have the ball in your hands. This relates back to reason #1 - working almost exclusively on things that simply won’t transfer to the game. 3. False sense of confidence Repeating the same dribble move (with no defender) 30 times in a row will lead to some level of improvement at that task. The player will be cheered on by their trainer and they will feel as if they are getting better. Unfortunately, it’s a mirage. They have improved their ability to perform a predetermined cross-over at the cone and shoot a layup. So they have improved at something. And that something provides confidence in their competence to perform that rote series of skills. However, it all comes crashing down when they have to perform it in a game scenario. As I outlined in reason #1, they are working on skills in a way that doesn’t simulate the randomness of a game. The trainer-player relationship is also tricky because the trainer needs to legitimize their role by doing things over and over so the player (and parent) feel like they are improving (and gaining confidence). True learning and improvement is messy but the optics of that aren’t ideal for a parent paying $100+/hr for their child to get better (or at least look like they are improving). All that being said, like most things in life, there are exceptions to the rule… 1. If a player is wanting to improve their shooting then there is value in having someone knowledgeable work personally with them on a technical skill like shooting. Although, after 2-3 sessions there are diminishing returns. The player should know what the “lynchpin” techniques they need to be working on to improve their shooting consistency after a few 1on1 sessions. Then it’s up to them to get the repetitions and work on it on their own. 2. If a player is 16+ years old and would benefit from the expertise of someone that can work with them closely to develop some “micro habits” in how they work on their skills. I would still say that you’re mostly paying for the motivation of having to show up to a skill workout since you’re booked with a trainer. It’s similar to the value that most personal (strength & conditioning) trainers provide - it’s the accountability you're paying for…not necessarily the results you are getting as a direct result of their expertise. However, if a player is only working on their game when their trainer is around then they’ll never be very good anyways. Now that you’ve heard why I think 1on1 training is highly inefficient for most players it’s only fair to provide some alternatives. I’ll suggest a few: 1. Small group training (3-6 players) allows for defenders to be part of the skill development while still providing an intimate setting so that the coach can provide real-time feedback to each individual player. 2. Large group training (15-30 players) allows for the same benefits as small group training with perhaps a little less personal feedback. An advantage of this form of training is there is a higher chance of grouping up with players of similar ability and size (due to more players being present). 3. Pick-up/scrimmaging at your local park or community centre. The best way to improve is to play live basketball against bigger/older/better players. You learn how to be effective in different environments and develop creativity that is hard to do in highly organized settings. Let me know what you think in the comments below! This post was written by Right Way Basketball founder, Mike Kenny, a former USPORTS National Champion, current coach educator, clinician and teacher of the game. Teaching Shooting: A Coach's Guide Indeed, the game has changed. There is a premium placed on being able to shoot the basketball (particularly from the 3-pt line) regardless of size or position. It’s a fun time to play as it’s most players favourite skill to practice but yet still an area that most coaches would describe as lacking in their players. So, why the disconnect? Shouldn’t players be improving their ability to shoot if it’s a fun skill to practice and also a major focus for coaches in today’s game? Let's dive in... Here are 5 things that will help you develop the shooters you've always wanted. Ask - don’t just tell In an earnest effort to help you may be tempted to blurt out all of the shooting advice you’ve ever heard to the player in front of you. There are a few problems with this approach - we simply can’t effectively process and apply more than 1-2 pieces of feedback at once. The player is also just a passive recipient of information and not actively part of the learning. Ask the player a question instead - what is your most common miss? When you land do you feel balanced? How could you get more arc on that shot? It takes more time but the learning will be more deep. And ultimately the best coaching means you (as the coach) eventually render yourself useless (or close to it). A player that can self-correct and figure things out on their own will improve at a faster rate than one who always needs the coach present. Simplify “You need to make 500 threes per day to be a great shooter”. A common phrase uttered, tweeted and repeated in basketball circles. Obviously repetition is an important element to improving in pretty much any area of life, particularly for a skill as technical as shooting a basketball. But like most “rules” there is room for interpretation. I’ll come right out and say it - players do NOT need to make 500 threes per day to become an elite shooter. But here’s the kicker - they need a simple and repeatable shooting stroke. To put it plainly - a player with more moving parts in their shot will need to practice more than someone with an uncomplicated shooting stroke. For this reason, our goal should be to help players simplify their shooting mechanics. One size does NOT fit all There is no one perfect shooting form. The goal is not to create a team of players that all shoot like Steph Curry or Duncan Robinson. Players have different biomechanics and limitations so it’s our job to work within those when we’re communicating advice and designing drills to improve habits. There are universal principles of shooting that are helpful to follow but oftentimes they won’t look identical when being performed by different players. Teaching shooting is more art than science. Mindset The difference between good shooters and great ones is their mindset. Confidence comes from 2 things: 1. Preparation (putting in the time to practice) and, 2. What you think about - assist to PGC Basketball on these. Assuming players are putting in the time and effort to practice then the major hurdle to confidence is what goes on between the players ears. One of our jobs should be to give practical tips on how players can re-shape or refine their self-talk. An example may be directing that player to remember what it felt like when they were shooting without thinking about it - perhaps a game when they made most of their shots. This process is often one of trial and error but must be undertaken and focused on if we’re to develop truly great shooters. Schedule the time It seems obvious but many coaches simply don’t allot enough shooting time into their practices. The realities of a season and the technical/tactical (offensive sets, defensive pressure, inbound plays etc.) can choke out the amount of time we dedicate to shooting at practice. Great shooters will always put in the time outside of team practices but if we’re agreeing that there is a premium placed on being able to shoot why aren’t we dedicating more time to it? A great offensive set only works as well as the players who can put the ball in the hoop. As a baseline, players should be getting 200 shots off every practice. The next layer is to track results and ensure players are competing when they shoot. If you want more shooters, then focus on it...every practice. We hope these 5 points will help you better teach shooting to your players. Please comment or use the contact tab to discuss any of this further. We’d love to hear your thoughts! This post was written by Right Way Founder and Shooting Coach, Mike Kenny, a former USPORTS National Champion, current educator, coach and clinician.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed